Since 2016 The Newbury Society has taken part in a scheme to erect blue plaques across Newbury to mark significant local people, places and historical events.

Click on the each of the tabs below to find out more about each blue plaque and the reasons behind its creation.

At the bottom of the page is a map that shows the location of each plaque, making it easy to find them in person.

- Stuart Rome

- John Winchcombe II

- Francis Baily

- Albert Alexander

- George & Pelican Inn

- James H. Money

- Brewing industry (former South Berks brewery)

- Elsie Kimber

- Didcot, Newbury & Southampton Railway

- Plenty Ltd

- Lottie Dod

- Walter Money

- First UK mobile phone call

- Esther Jane Luker

- Doris Page

- James Bicheno

- Professor John Newport Langley

- Thomas Hardy

- The Plaza

- France Belk

Stewart Rome was a British film actor who achieved national fame during the silent film era and successfully made the transition to talkies. He was born and brought up in Newbury and eventually retired here. His versatile and prolific career is credited with over 160 films.

He was born Septimus William Ryott, the son of an auctioneer of the same name who died aged 40 and who was the son of Robert Ryott, a Newbury pharmacist who served as Mayor of Newbury in 1869 and 1870. Septimus Jr was brought up by his mother Alma and educated at St Bart’s. He trained as an engineer, but in 1907 commenced an acting career in Australia. His film debut on his return to England occurred with the Hepworth Film Company and the film “Justice” in 1914. He assumed the professional name “Stewart Rome”. He proved an immediate success, making several films a year, and in 1915 a poll of cinema goers voted him Britain’s most popular film actor. He also served in World War I in the Second Oxon and Bucks Regiment.

The following account of his early life was given in an interview with the Newbury Weekly News on 18 August 1921:

‘“I am the only actor of the family, the others are all interested in engineering or farming. They tried to make an engineer of me, but I could not tie myself down to anything so prosaic. I belonged to a Dramatic Club in Newbury, and I’m afraid that I thought more of my small efforts than of swotting for the exams I should have passed, but didn’t. After a while, we fought out the question of my profession, my parents and I, and I won. I started my stage career in musical comedy, didn’t like it, and was glad to on tour in more dramatic work”

He travelled with a repertory company in the East, returned to England, had a breakdown, and emigrated to Australia; went in for stock farming and came out penniless. Roughed it in the Bush, was a waiter in Perth and a stock hand at Sydney, came back home, tool up film work, and made good. Now he’s a star.’

According to his obituary in the Newbury Weekly News (4th March 1965), he was the first real star of the British cinema. His characters included amongst others a tramp, explorer, Harley Street doctor, prize fighter, race horse owner, clergyman, and fisherman. His film “Comin’ Thro’ The Rye” (1916) was the first to be given a Royal Command Performance.

Bryony Dixon, Curator of Silent Film at the BFI National Archive, states: “Stewart Rome was an important star of British film in the silent and early sound eras. He made more than 160 films between 1914 and 1948 – specialising in debonair rogues and military types – he also played many leading man roles. My personal favourite is his character in The Ware Case (1928), an adaptation of a successful country house mystery play, where he is called upon to have a nervous breakdown on camera. Over thirty film productions featuring Rome survive at the BFI National Archive. Later in his career he played character roles – judges and generals but always in England. Unlike many of his contemporaries he didn’t leave Berkshire for Hollywood.”

His success continued as a freelance after World War I, with films in Germany as well as in Britain. The transition to talking films in 1929 saw him mainly portrayed in fine gentlemanly roles in the 1930’s and ‘40’s, until his retirement to Newbury in 1950 with the movie “Let’s Have a Murder”.

In the late 1930’s his address was “Rooks Way”, Hill Green, Peasemore. His later Newbury address was 317 Andover Road.

The building to which this plaque is attached functioned as a silent film cinema, the Newbury Picture Palace, from 1910 to 1934.

“Jack of Newbury” or John Winchcombe II (c.1489-1557) was a leading cloth-producer in the reign of Henry VIII, when woollen cloth was the country’s most important export. For a time, he was the leading figure in England’s leading industry.

The many different cloths produced at the time were dominated by broadcloths and kersies, and current evidence shows Winchcombe producing on an industrial scale: over 6,000 kersey cloths each year in the 1540s. Each cloth was about a yard (0.9m.) wide, and 17-18 yards long. The scale of his production is also indicated by details of the dyeing process. Woad was his most important dye, normally delivered by the cartload. One order survives for 541 cwt, or over 27 tons of woad.

Many people were involved in the production processes, which included spinning and weaving. Fulling took place in local mills and the finished kersies were exported via London to Antwerp, where they were recognised in the 1530s and 1540s as the best of their kind. Although Winchcombe has sometimes been credited with founding England’s first factory, no documentary evidence of a weaving workshop has yet been traced. However, the quantity of cloths produced suggests a workshop of perhaps 30-50 looms.

In the language of the time, he was a “clothier,” organising the production of cloth which was then sold in his name. In the 1530s and 1540s he led a national campaign to persuade Henry VIII to change the law on the making of woollen cloth, heading a group of clothiers from six counties – a campaign which was ultimately successful.

The Newbury area had produced cloth since prehistoric times; and would continue to produce cloth long after Winchcombe’s death. But it was only in his lifetime that Newbury reached national importance in this field. This prominence was real but short-lived.

In Henry VIII’s reign, John Winchcombe combined a role as a cloth-producer with that of one of the county gentry for Berkshire. He was among those present for the reception of Henry VIII’s fourth wife Anne of Cleves, and his personal contacts included Sir Thomas Gresham and the Protector Somerset. He spent over £4,000 on the purchase of property including the manors of Thatcham and Bucklebury, and held a portfolio of other property mainly in and around Newbury. He was a Member of Parliament and a Justice of the Peace.

As one of the county gentry, John Winchcombe led Newbury men to war to fight for Henry VIII, including to the siege of Boulogne in 1544. He was granted a coat of arms, and had his portrait painted in 1550.

His home in Northbrook Street filled the area between Jack Street and Marsh Lane (now mostly occupied by Marks & Spencer, and previously by the Jack Hotel), and here he welcomed the future Protector Somerset. It consisted of timber-framed buildings ranged around courtyards. A fragment of this extensive home survives on the corner of Marsh Lane, complete with carvings and mouldings. Other carvings now at Sudeley Castle in Gloucestershire. It is on this surviving part of his house that the blue plaque has been placed.

A fictionalised story of his life, written by a contemporary of Shakespeare, with published in the 1590s. This was “The Pleasant Historie of John Winchcombe, in his younger years called Jack of Newbury…” by Thomas Deloney. Thomas Fuller described Winchcombe in the 17th century as “…the most considerable Clothier (without fancy or fiction) England ever beheld.” Winchcombe has been frequently confused with his father, who died in 1520 and was also a clothier.

David Peacock 2017

Francis Baily (1774-1844) was an eminent astronomer, the son of Richard and Sarah Baily. The Bailys are a Thatcham family, and their family vault lies at St Mary’s Church, Thatcham. However, Richard Baily had moved to Newbury to engage in business as a banker, coal merchant, and barge master, and served as Mayor of Newbury 1773-74. Francis was born at his house at 62 Northbrook Street (since rebuilt).

After a tour in the unsettled parts of North America, Baily entered the London Stock Exchange in 1799. He earned a high reputation as a writer on life contingencies and amassed a fortune which enabled him to retire from business in 1825, to devote himself wholly to astronomy. He took a leading part in the foundation of the Royal Astronomical Society in 1820 and was elected its President four times (1825–27, 1833–35, 1837–39 and 1843–45). His fame as an astronomer rests on his discovery of “Baily’s beads” in 1836. During an eclipse of the sun by the moon, the irregular shape of the moon’s limb allows beads of sunlight to shine through in some places around the moon’s profile, but not in others. He observed the phenomenon again at Pavia during the solar eclipse of 1842, starting the modern series of eclipse expeditions.

In other work, Baily superintended the compilation of the British Association’s Catalogue of 8377 stars (published 1845), and revised the catalogues of Tobias Mayer, Ptolemy, Ulugh Beg, Tycho Brahe, Edmund Halley and Hevelius. He completed Henry Foster‘s (1797-1831) pendulum experiments, deducing from them an ellipticity for the earth of 1/289.48. This value was corrected for the length of the seconds pendulum by introducing a neglected element of reduction, and was used in 1843 in the reconstruction of the standards of length. His laborious operations for determining the mean density of the earth, carried out by Henry Cavendish‘s method (1838–1842), yielded the authoritative value of 5.66. He published at his own expense a detailed account of the work of the first Astronomer Royal, Sir John Flamsteed.

Baily lived at 37 Tavistock Place, London. He was elected a Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1832. The lunar crater Baily was named in his honour, as were the rigid and thermally insensitive alloy (Baily’s metal) used to cast the 1855 standard yard, and the Francis Baily Primary School in Thatcham.

Albert Alexander, an Abingdon Policeman who had served in Newbury, was the first person to be treated with Penicillin. Although unfortunately the treatment did not succeed, his place in the history of antibiotics is secure.

He was born in 1897 in Woodley, Reading, the fourth child of Edward Alexander, a farm labourer, and his wife Emma. He joined up at World War I, and served in the Army Service Corps, 101st Company ASC, 14th Divisional Train, providing horse transport to the front line in France or Belgium.

In 1921, Albert joined the Berkshire Constabulary, and from 1923 to 1929 was stationed in Newbury. In 1924 he married Edith Mary Deacon at St Mary’s Church, Speenhamland. They lived in Newbury and had two children. In 1930 he was transferred to Thatcham and in 1937 to Wootton, near Abingdon.

At the outbreak of World War II, he was assigned to the Force’s Mutual Aid Team, on standby duty to go anywhere in the country. On 30th November 1940 he was in Southampton supporting the Southampton Police, when he was injured in an air raid on the Police Station. He developed blood poisoning and was transferred to the Radcliffe Infirmary in Oxford, where it was decided to treat him with Penicillin. At the time of his treatment the effects of a large-scale injection were not known, but Albert’s Staphylococcus and Streptococcus septicaemia was so severe that the action was considered justified. He immediately showed a great improvement, but sadly not enough Penicillin had yet been isolated and he died on 15th March 1941.

Albert was buried in the Newtown Road Cemetery, where he was joined by his wife Edith Mary, who died in 1985 aged 89.

Sources:

National Association of Retired Police Officers May 2004

Friends of Newtown Road Cemetery

British Medical Journal 22-29 December 1984

Ancestry

The George & Pelican was Newbury’s most famous coaching inn. It was created

around 1730 by the amalgamation of The George and The Pelican, a few years before

the Great Bath Road (the modern A4) was fully ‘turnpiked’ in the 1740s. The

creation of turnpike trusts was an early form of privatization in which companies

took over the maintenance of major roads in return for the right to charge users a

toll to use them. It was a great success and resulted in a massive improvement in the

standard of roads, which enabled a new age of travel – the coaching era. The inn was

in Speenhamland, which was not then within the Parish or Borough of Newbury,

although clearly a part of the overall town.

It was not the grandest inn or hotel in Newbury. It catered for a wider section of the

community than the very rich and, as a result, it was a more viable business, whilst

seeing its fair share of custom from the highest echelons of society. During its

heyday it was visited by many notable travellers, including King George III and Queen

Charlotte, Charles Dickens, Samuel Coleridge, William Cobbett and the actor James

Quinn – who is credited with the witty epigram:

The famous inn at Speenhamland

That stands below the hill

May well be called the Pelican

From its enormous bill.

In 1795 local MP, Charles Dundas, chaired a meeting of Berkshire JPs at the George &

Pelican that decided to address the pressing issue of agricultural poverty through a

widely adopted system of relief known as the Speenhamland System (taking its name

from the inn’s location).

During the golden age of the coaching era the George & Pelican was owned and run

by George & Eleanor Botham and was a large business. They owned over 200 horses

which would could be rented by travellers or coaching companies. The inn had

stabling for 300 horses, a bowling green and pleasure gardens on the north side of

Speenhamland Backway (now part of Pelican Lane) to the rear of the inn. When a

Parliamentary select committee was inquiring into the optimum road-making

technique George Botham was called to London to give evidence. He spoke in favour

of John McAdam’s process, which was later developed into tarmac.

The opening of the Great Western Railway in 1841 heralded the end of the coaching

era in this part of the country, the trade shrank immensely, and Eleanor Botham

(George had died a few years earlier) went bankrupt. The inn struggled on for a

while, eventually closing in 1869 when the final proprietor, Henry Thomson, moved

to the Three Tuns (now the Elephant in the Market). The stables then became a

livery business that continued trading well into the 20th century.

Phil Wood (2019)

James Henry Money was born on October 14, 1834, at the Dene, Oxford Road, Donnington (also known as Donnington Dene), near the Castle pub. He was the son of John and Maria Money; he had two older sisters, and was the second of three brothers. His younger brother was Newbury historian Walter Money.

His father ran a brickworks at Donnington before moving on to create a surveyor’s and then an architect’s business. His mother’s father was also a surveyor.

On leaving school James H. Money trained as an architect, articled to Cooper & Kent of Gray’s Inn, London. At this time his designs were selected in competitions for cemetery buildings at Watford, Ipswich and Keighley in Yorkshire.

On returning to Newbury, he joined his father’s practice in the 1850s, and had effectively taken over by the end of the 1860s. John Money died in January 1874, but had not been involved in the business for several years before then.

James H. Money had a long and productive career: he was active as an architect for over 50 years, from the 1850s until shortly before the First World War. In 1862 he married Martha Joan Vincent, daughter of Newbury solicitor Frederick Vincent.

In 1864 his office was at 34 Northbrook Street (also home to the printers who established the Newbury Weekly News), and his home was in Enborne Road. Later in the 1860s he acquired buildings in the Broadway, including York House, which became his long-established office. His home moved to The Shrubbery, Oxford Road (now Wessex House, opposite Waitrose).

His designs were numerous, in many different styles. They included cottages, pubs, breweries, shops, schools, chapels, church restorations, and extensions to country houses, almost all in the Newbury area, with more around Andover and a school in Devon.

His most prestigious projects were the town halls in Hungerford and Newbury, the Falkland Memorial, and Oddfellow’s Hall in Newbury. Hungerford Town Hall was built 1870-71; Newbury 1876-81, with an extension in 1909-10; the Falkland Memorial at Wash Common, commemorating the first battle of Newbury in 1843, was unveiled in 1878; and Oddfellows Hall in Craven Road, Newbury was built in 1886.

His wife Martha died in 1893 at The Shrubbery. It was after this that he moved his home to York House in the Broadway (now Thames Court), where his office had been for many years. He died on June 21, 1918 at his home in Newbury. The funeral took place at Shaw Church, and there is a memorial cross to him and his wife in the churchyard. He had at least 10 children (one son and nine daughters surviving in 1918).

David Peacock, July 2017

Brewing on a commercial scale began to establish itself as a major industry in the late middle ages, following the introduction of hops into the brewing process. Hops add bitterness to the brew, but also act as a preservative, meaning that there was more time to transport the beer to retail premises where it had a longer shelf life. However, it would be confined to larger towns and cities until an effective means of distribution was available to enable the brewer to reach a larger market. The first evidence of commercial brewing in Newbury was in 1643, when 34 publicans, and three brewers were amerced (fined) at the manorial court for taking excess profit in beer.

In 1723 the River Kennet was made navigable to Reading, meaning that the country’s largest market for beer, London, was within reach of Newbury. The earliest records of the ‘Navigation’ show that almost immediately at least one Newbury brewer, John Townsend, was shipping beer in bulk to the capital where Newbury beer was soon a popular tipple.

The Beer House Act of 1830 was an attempt by Parliament to break the monopoly of the brewers. The idea was that their grip on the trade, largely gained though the local monopolisation of pub licenses, would be broken by allowing anyone with suitable premises to sell beer or cider, preferably brewed on the premises. However, the brewers soon became the suppliers of the new premises as well as the old and the act failed in its intent. Nevertheless, it was partially successful in increasing competition since numerous new breweries were opened to exploit the increased market. Some of these had short lives but, by the time the Act was repealed in 1869, there were nine commercial breweries in Newbury.

From the 1890s the numbers were diminished through mergers and takeovers from which the South Berkshire Brewery Company in West Mills emerged as the major player. By 1920 there were only four breweries left; in that year the South Berks was purchased by H & G Simonds of Reading, which also bought the Newbury Brewery Company of Northbrook Street in 1930 and Adnams’ Eagle Brewery of Speenhamland in 1936. The takeover of Adnams’ marked the end of brewing in Newbury since the fourth of the last brewers, Finn’s Phoenix Brewery of Bartholomew Street had been acquired by Ushers Brewery from Trowbridge in 1926.

The blue plaque marking the importance of the brewing trade to the town has been placed on St Nicolas House in West Mills. This splendid Grade II* listed building was built in the 1730s as a home for Samuel Slocock, proprietor of the West Mills Brewery.

Phil Wood (2019)

This plaque commemorates Elsie Kimber (1889-1954), who in 1932 was elected as the first female Mayor of Newbury since the Borough was created in 1596. The plaque is located at 64 Bartholomew Street, now Hillier & Wilson Estate Agents, but formerly Kimber’s Grocery and Provision Merchants, informally called “Kimber’s Corner”, which she ran from 1939 until her retirement in 1953.

Elsie Kimber was a pioneer in our local government. The road had been steep. Although women had been permitted to be elected as local Councillors and to serve as Mayor and Aldermen in 1907, full national gender equality for voting purposes was only granted in 1928. Elsie was elected the first female Newbury Town Councillor in 1922 and was appointed its first female Alderman in 1943. The next female Mayor, Ethel Elliott, was not elected until 1953, and it was not until 1993 that female Mayors were addressed as “Madam Mayor”. Until then, the term “Mr Mayor” was so ingrained that it was used even for women.

Elsie Kimber was born at 64 Bartholomew Street and was one of the first intake to the Newbury County Girls’ School when it opened in 1904. She joined her father, Ernest Kimber, in his grocery business and ran it after his death until she retired. She was also the first woman delegate to the All England Grocers’ Conference. During the Second World War she served as an ARP Warden. Her interests as a Councillor included housing, slum clearance, public health and education. She taught swimming to children, and her reputation was of “one who had an infinite capacity for taking pains”.

In his 1990 autobiography, the author Richard Adams wrote: “Alderman Elsie Kimber was a legendary figure in Newbury. She had rimless glasses, wore a heavily-skirted, brown belted garment, sandals and no hat, and she rode a motor-bike. She was emancipated, bizarre, no fool and excellent company, even to a small boy. To me it seemed entirely natural that the Mayor should look somewhat unusual. I vaguely supposed that that was what mayors looked like.”

This plaque commemorates the central role that was performed by the former Didcot, Newbury, and Southampton Railway in conveying service personnel and military materials from the Midlands and the North of England to the Port of Southampton in preparation for the D-Day invasion of Nazi-occupied Europe on 6th June 1944. The plaque is located outside Newbury Railway Station, by kind permission of Network Rail and Great Western Railway.

The DNS Railway constituted the heavy transport link for this vital supply. At its peak, it carried 120 train movements a day. To accommodate the traffic, the line between Didcot and two miles south of Newbury was doubled. Despite its name, it terminated at Winchester, and depended for the final part of its route on other railway lines. Unfortunately, it never proved profitable from its opening in 1882/1885 or after 1945, and was eventually closed in 1964.

Newbury Railway Station was first built in 1847. It was rebuilt as the present building between 1908 and 1910, to handle the traffic through Newbury on the Didcot, Newbury and Southampton Railway, the Great Western Railway, and the Lambourn Valley Railway.

Plenty’s was founded in Southampton in 1790 by William Plenty (1759-1832), a millwright and agricultural engineer, who shortly afterwards moved the business to Cheap Street in Newbury. In 1800 he patented an iron plough, which was recognised as being more manoeuvrable and economical in use. In 1817 he launched a new design of lifeboat, which was exceptionally stable and seaworthy, and was adopted by the body now known as the Royal National Lifeboat Institution. 11 were stationed round the British coast and saved many lives at sea.

William was succeeded in management of the business by his sons James Shergold Plenty (1811-51) and Edward Pellew Plenty I (1816-98) (named after Admiral Sir Edward Pellew). In 1865 they diversified by patenting a marine steam engine, and in 1880 the company was added to the Admiralty list for supply of steam engines, used particularly in Royal Navy picket boats and in submarines from 1885-87. The company supplied marine engines world-wide and in 1890 was incorporated as Plenty & Son Ltd. The premises became known as the Plenty Eagle Iron Works. Subsidiaries were founded in Glasgow, Southampton, and overseas.

Edward Pellew Plenty I was elected Mayor of Newbury in 1865-66. He partially retired in 1868 to “Budd’s Farm” in Burghclere, which he had inherited through his wife Caroline Simmonds, the niece of William Budd, Solicitor and Mayor in 1789-90. He experimented in agricultural improvements and retired fully in 1884. His son Edward Pellew Plenty II had succeeded him, but in 1899 absconded with £4600 of the company’s assets. The other Directors Harry Wethered and the second Earl Russell then appointed Edward Plenty II’s son Edward Pellew Plenty III (1868-1949) (known as Jack Plenty) to head the firm. Jack Plenty had a son Edward Pellew Plenty IV (1897-1921), who achieved a brilliant career in the Royal Flying Corps, being promoted Lieutenant in 1915 and Major in 1918, but very sadly died in the influenza epidemic of 1921. The family’s connection with the firm therefore ended in 1949.

Plenty’s diversified into a wide range of products, including iron bridges, and in 1920’s adopted diesel technology, with engines for not only for ships, winches, and compressors, but also power stations. In 1935 it commenced production of a wide range of rotary pumps. Filters were added in 1951 and mixers in 1955 as it focused on fluid processing products. In recent decades (1970s onwards), some of Plenty’s work was in connection with North Sea oil.

In 1965 the company moved from Cheap Street to its present premises in Hambridge Road. In 1969 it was acquired by Booker McConnell and in 2001 by SPX Flow Technology, an international company with $2 billion in annual revenue and operations in 30 countries. SPX Flow Technology’s pumps, mixers, and filtration products for the oil and gas, water, food, and chemical industries bear the Plenty brand.

Anthony Pick

10th October 2019

Sources:

Newbury Advertiser 22-29 September 1987.

Newbury Weekly News 26 February 2015 (for E.P. Plenty IV).

Berkshire Record Office (Ellie Thorne).

Charlotte (Lottie) Dod was an outstanding female British sportswoman of the pre-First World War era, and one of the most versatile of all time. She was born in Cheshire, the daughter of a wealthy Liverpool cotton broker. She initially excelled at tennis, winning the Wimbledon ladies championship in 1887, 1888, 1891, 1892, and 1893. Proceeding to other sports, in 1904 she won the British Ladies Amateur Golf Championship and played twice for the England women’s national hockey team, which she helped to found. In 1905 she and her brothers moved to Edgecombe, Andover Road, Newbury (now the site of Woodridge House) and lived there until 1913, when they moved to Devon. While in Newbury she joined the Welford Park Archers, and won the women’s silver medal in archery at the 1908 Summer Olympics. Other sports which she mastered were the Cresta Run, skating, rowing, sculling, horse-riding, mountaineering, and billiards.

Newbury historian Walter Money was born at Donnington Dene, Oxford Road, Donnington in August 1836. He was the son of John and Maria Money, and his brother James H. Money went on to become an important local architect.

As a young man, Walter Money trained as an architect. In 1865 he married Charlotte Ann Butler, and the couple lived for many years at Herborough House in Bartholomew Street. He was there in 18801, still there in 18962, but gone by 19003.

It was while living at Herborough House that he published some of his best-known books, including his monumental History of the ancient Town and Borough of Newbury in the county of Berks, or, more simply, History of Newbury (Parker & Co, Oxford 1887); and The First and Second Battles of Newbury and the Siege of Donnington Castle (W. J. Blacket 1881).

Herborough House was at 122-123 Bartholomew Street, in its later years used by Nias, and then demolished as part of the development of the Kennet Centre.

Walter Money joined the Newbury District Field Club in 1875, and became one of its leading members (Hon. Secretary from 1879 to 1893). He was a churchwarden of St. Nicolas Church. In 1878 he was elected a member of Newbury Town Council and he was a member of Berkshire County Council from 1889 to 1897. He became a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries (FSA), and was a member of the Berkshire Archaeological Society, and local secretary for the National Trust.

Apart from the books mentioned above, a condensed Popular History of Newbury followed in 1905, along with several more books, a number of booklets, and a long series of articles for newspapers and periodicals, including many for the Newbury Weekly News.

In retirement, he went to live at Shaw Dene. His wife Charlotte died in 1922. He died on October 18, 1926, aged 90, at a nursing home in St. John’s Road. He was buried in the Newtown Road cemetery. In his memory, Newbury Museum (as it was then) was extended with a new building added to the east side of the Cloth Hall.

1. Walter Money letter of Dec 27, 1880 written from Herborough House. In private collection.

2. Cosburn’s Directory of Newbury 1896 p. 314.

3. Cosburn’s Directory of Newbury 1900 p. 314.

Press report dated 3rd January 1985 courtesy of the Newbury Weekly News

Michael Harrison secretly left his family’s 1985 New Year’s Eve party at their home in Surrey in the UK to surprise his father, calling him from London’s Parliament Square. Harrison made the historic call from one of the first mobile devices – a Transportable Vodafone VT1, which weighed 11lb (5kg) and had around 30-minutes of talk time. Harrison recalls that the line was crystal clear, although the excited shouting of New Year’s Eve revellers in London created considerable background noise.

As Sir Ernest Harrison answered the phone, Michael said: “Hi Dad. It’s Mike. This is the first-ever call made on a UK commercial mobile network”. At the other end of the line, champagne corks popped and photographers captured the moment – the culmination of three years of hard work since the bid was made to win the licence in 1982.

Days later, a large crowd gathered at St Katherine’s Dock in London to watch comedian Ernie Wise make the first public mobile phone call. Wise brought the same Transportable device to St Katherine’s Dock in London in a 19th century mail coach, using one of the oldest forms of communications – sending a letter – to highlight the speed and convenience of these new mobile phones. Ernie Wise’s call was received at the original Vodafone headquarters, where a handful of employees were based in an office above an Indian restaurant in Newbury, Berkshire.

Heavy and cumbersome, the first generation of mobile phones were sold in the UK from 1984 – before the first products were even available and before the network was officially live. Such was the demand for a fully portable, cellular phone that more than 2,000 orders had been taken by the Vodafone sales team before Michael Harrison made his call from Parliament Square. By the end of 1985, over 12,000 devices had been sold. All were far from portable and cost around £2,000 – equivalent to roughly £5,000 when taking the inflation rate in to account. However, the early mobile phones symbolised a revolution in communications and were instantly desired by the emerging ‘yuppy’ set, whose love for the brick-like devices was documented in films and TV shows, from Wall Street to Only Fools and Horses. Ferrari-driving executives in the first wave of adverts particularly appealed to this market. “You can be in when you’re out” declared full-page ads, created by advertising agency Saatchi & Saatchi to run in every major British newspaper.

Thirty years later, Vodafone’s technology, once favoured by a select few, now plays a central role in the lives of more than 400 million people on every continent.

The plaque was unveiled by Sir Christopher Gent, former Chief Executive Officer of Vodafone, with the support of the Mayor of Newbury, Cllr Julian Swift-Hook.

Source: Vodafone press release 31 December 2014, edited.

Esther Jane Luker (1872-1969) was seen as an education pioneer, after Newbury Girls’ School became the first school in the town to offer secondary education for girls to university standard.

She was headmistress from 1904 until 1933 and by the 1920s, the school’s girls were gaining entrance scholarships to Cambridge.

Known as Jane or “Miss Luker,” she was educated at Dulwich High School and then at Girton College, Cambridge, where she gained the Mathematical Tripos with honours. She was not awarded her B.A., because this was decades before Cambridge awarded degrees to women. She was also a keen hockey player, and college games captain.

After teaching at schools in Sheffield and Winchester, she arrived in Newbury in 1904, when Newbury Girls’ Grammar School was opened at the Technical Institute in Northbrook Street with less than 40 pupils. Her aim in Newbury was to create the kind of school which would encourage girls to go on to university.

Purpose-built buildings were erected on the Andover Road, and the school transferred in 1910. Miss Luker moved into the house next door, Tirhoger, with Maud Cobbe, the deputy headmistress, and boarders. By 1914 the school had 250 pupils. Miss Luker had her own style; believing that the best learning was that pursued for the love of it. She retired in 1933, leaving for the Chichester area with Miss Cobbe, and she died in 1969 at the age of 97.

Doris Page (aka Ann Armstong) (1925-1991) became a pioneer campaigner and journalist for disabled people.

She contracted polio in 1955 and was confined to an iron lung for the rest of her life. With the support of her husband Ken, she returned home to 39, Essex Street, Newbury in 1957 and campaigned tirelessly for the necessary infrastructure to enable disabled people to lead a viable home life, as a founder member of the charity “Independence at Home”.

She took a postal course in journalism and started to write on disabled issues for the local and national press, under the pen-name “Ann Armstrong”, using specialist equipment which made writing possible. From 1963-88 she was editor of “The Responaut” magazine (the name may be a contraction of “respiratory” and “astronaut”).

In 1968, Doris was awarded the MBE for her services. She wrote two books – “Patient’s Prospect” and “Breath of Life” – which were serialised on BBC Woman’s Hour.

James Bicheno was a local campaigner against the slave trade in the late 18th century, actively promoting two petitions from Newbury to Parliament to ban slavery. He was also the Baptist minister of Newbury for 27 years.

He was born in Over, Cambridgeshire, in January 1752, and was baptised into the Baptist church in Cambridge in 1768. He attended Cambridge University, but left university after a year in 1769, the same year he was “cut off” by the Baptist church.

About 1770 Bicheno travelled to America, and it was later reported that he had been sold as an indented servant in Virginia, after falling victim to deception. His master is said to have been a member of the Virginia Council of State or “Governor’s Council”. One account states that after various difficulties, including time spent living with his master’s slaves, Bicheno was accepted into his master’s household as his children’s tutor. In due course he was redeemed by his friends and returned to England.

He re-joined the Baptist church in Cambridge in 1774 and then trained as a Baptist minister at Bristol Baptist College from 1776, ordained in 1778. The same year he was appointed Baptist minister at Falmouth, and after 18 months there became the Baptist minister at Newbury in 1780. He continued as Newbury’s minister for 27 years, until he resigned in 1807.

The Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade was formed in 1787, and the following year organised its first national campaign of petitions to the House of Commons for the abolition of the trade. Rev. James Bicheno is understood to be the author of an advertisement in the Reading Mercury (then the local newspaper) in March 1788, which appealed to “the inhabitants of Newbury” and described the conditions of slavery: “Hundreds of men, women and children are crowded into the hold of a ship, exposed to the despotic will, the lust and cruelty of unfeeling seamen; and all this is aggravated by the dreadful uncertainty which lies before them. multitudes perish on their passage; those who survive are sold as cattle, to be slaves for life…”

The advertisement resulted in a public meeting held on April 7, 1788 at the Mansion House in the centre of Newbury (Newbury’s town hall at the time). The Mayor of Newbury, aldermen, burgesses and inhabitants of Newbury were “deeply impressed with the injustice and inhumanity of the Slave Trade,” and called for it to be stopped by any practical means. They petitioned the House of Commons to take action “…for bringing to a speedy end, the horrors of a commerce which is disgraceful to our national character, and by which we become the instruments of misery to innumerable multitudes of our fellow creatures.”

The meeting gave a vote of thanks to the Mayor, John Hasker, for agreeing to call the meeting, and to Mr Bicheno, “for his great attention to this common cause of humanity” (although in the newspaper report his name was mis-spelt as the “Rev. Bickens”). The petition was presented to Parliament, along with over 100 other petitions from all parts of England, but the House of Commons decided not to respond.

In 1792 Bicheno was one of ten people who called for a public meeting to consider a second petition. The meeting was held at the Mansion House on March 5, and agreed to present a petition to the Commons against “…the very great Enormity of this abominable Traffic in Human Flesh…” The petition described this as a trade “…which violates the most sacred Laws of Justice and Humanity, disgraces us as a People glorying in the exercise of Liberty and which dishonours us as Christians professing a religion that breathes Peace and Good Will to all Men.”

This petition was signed by 333 Newbury people, with the Mayor Joseph Toomer and Bicheno among those at the head of the list. It was handed over to Berkshire MP Winchcombe Henry Hartley, who with fellow MP George Vansittart was asked to present it to Parliament, which they did later in March 1792. This time the Newbury petition was one of over 500 petitions in a larger national campaign co-ordinated by the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade.

The continuing campaign had a major success with the Slave Trade Act 1807, but it was not until the Slavery Abolition Act 1833 (3 & 4 William IV c.73) that slavery was abolished throughout the British Empire.

In addition to being the Baptist minister, Bicheno ran a boys’ boarding school at Greenham House, then in Greenham. In 1783 he married Ann Hazell (1749-1814) at Wantage, and they had two children who survived to adult life: James Ebenezer Bicheno and Elizabeth Frith Bicheno (later Elizabeth Francis). He left Newbury in 1811 to serve the Baptist community in Aston near Witney, where his wife died in 1814. He returned to Newbury in 1819, staying in the town for the rest of his life. He died at home in London Road, Newbury, on April 9, 1831, and was buried at Wantage.

He published a number of religious books and articles, including 11 pamphlets relating Biblical prophecy to European events during the French revolutionary and Napoleonic periods. He was awarded a Master’s degree by Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island in 1796. He was also a very early supporter of the Baptist Missionary Society.

His son James Ebenezer Bicheno (1785-1851) became Governor of Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania), and the Tasmanian town of Bicheno is named after him.

Professor John Newport Langley (1852-1925), eminent physiologist born

in Newbury whose work helped lay the foundations of modern medicine

An eminent academic, John Newport Langley, Professor of Physiology at

Cambridge 1903-25, achieved ground-breaking work in two main areas

of physiology. He was born in Newbury and lived there until the age of

about 10, when he left to attend Exeter Grammar School.

He near-single-handedly established the physiology of the autonomic

nervous system, including the well know sympathetic ‘fight or flight’

response. He was also the first person to use the term ‘receptive

substances’ to describe receptor proteins in the cell membrane that

respond to external chemical signals such as hormones and

neurotransmitters. It is on this basis that much of modern pharmacology

and pharmaceutical drug development depends.

The plaque is located at 58 West Street, by kind permission of the

owners Newbury Samaritans. It was unveiled at 11am on Thursday 2nd

March by the Mayor of Newbury, Cllr Gary Norman. Langley’s home

was 50 West Street, part of the adjoining terrace, which was demolished

in the 1960’s.

John Langley was the son of a private schoolmaster. His uncle Rev.

Henry Newport was headmaster of Exeter Grammar School and had

previously (1848-52) been the first Headmaster of St Bartholomew’s

School, Newbury after its re-foundation. From taking his BA in 1875,

Langley engaged in a lifetime of research at Cambridge into

neurophysiology. In 1877 he was elected Fellow of St John’s College

and in 1883 Fellow of the Royal Society.

Thomas Hardy (1840-1928)

Location: The Chequers Hotel

Hardy’s final novel, Jude the Obscure, written in 1895, is in large part set in and around Newbury and Oxford, which appear under the fictional names of Kennetbridge and Christminster.

Kennetbridge forms part of Hardy’s fictional North Wessex region and is described as “ a thriving town not more than a dozen miles south of Marygreen [Fawley]”.

The Chequers Hotel is mentioned by name in the novel as a favourable place to stay.

It was the spring fair at Kennetbridge, and, though this ancient trade-meeting had much dwindled from its dimensions of former times, the long straight street of the borough presented a lively scene about midday. At this hour a light trap, among other vehicles, was driven into the town by the north road, and up to the door of a temperance inn. There alighted two women, one the driver, an ordinary country person, the other a finely built figure in the deep mourning of a widow. Her sombre suit, of pronounced cut, caused her to appear a little out of place in the medley and bustle of a provincial fair. “I will just find out where it is, Anny,” said the widow-lady to her companion, when the horse and cart had been taken by a man who came forward: “ and then I’ll come back, and meet you here; and we’ll go and have something to eat and drink. I begin to feel quite a sinking” “With all my heart,” said the other. “Though I would sooner have put up at the Chequers or The Jack. You can’t get much at these temperance houses.” Part Fifth: At Aldbrickham and Elsewhere, chapter VII

The blue plaque forms part of the Thomas Hardy Trail of sites commemorating the author’s work.

The Plaza

The Plaza was built in 1925 by Newbury businessman, Jimmy Tufnail (d. 1930).

It was originally a theatre: Iolanthe was one of its earliest productions. It was known variously as Tufnail’s theatre, the Plaza Theatre and the Plaza Ballroom.

Many emerging or famous bands played there during the 1960s and early 1970s, notably the Jimi Hendrix Experience, The Who and Cream

Over the years it served as a venue for a variety of events, including political rallies, jumble sales and country fair markets.

Jimmy Tufnail moved from Reading to Newbury in 1887, quickly building up his business empire from scratch, including several enterprises in the Arcade, Cheap Street and the approach to the railway station. Soon after the Plaza’s construction, he opened a cinema there and from 1930 it screened talking movies.

Several years later, Newbury Borough Council bought the Plaza and, until the late 1970s, the hall was used for staging events twice or three times per week.

In 1977 a business consortium proposed the purchase of the Plaza from the Town Council and its redevelopment as a nightclub, but lack of funding and local opposition put paid to the scheme.

Location: Situated at the bottom of an arcade of shops and accessed from 16-18 Market Place (now Bill’s Restaurant),

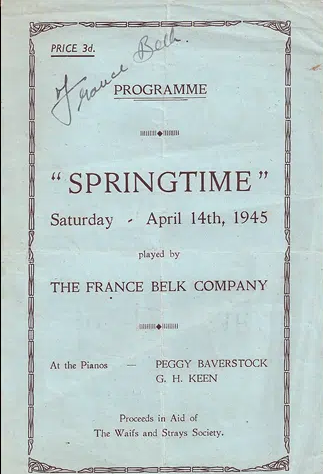

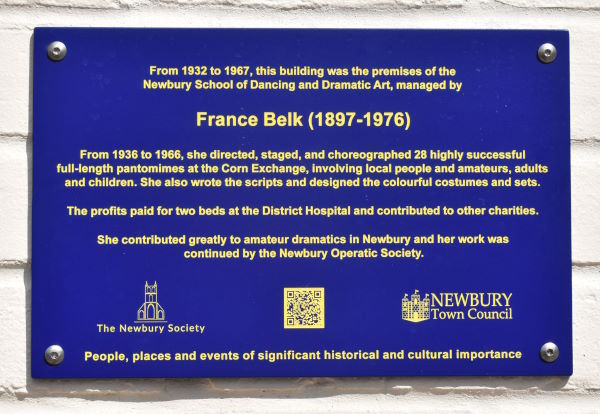

France Belk (1897-1976) managed the Newbury School of Dancing and Dramatic Art for thirty-five years (1932-1967), playing a central role in moulding dance and

amateur dramatics in the town and inspiring generations of performers.

She is renowned for staging and choreographing twenty-eight full-length pantomimes at the Corn Exchange in a thirty-year period starting in 1936.

The France Belk Company brought together both local adults and children in productions for which she wrote the scripts and designed the sets, as well as directing and appearing in them herself. These creations raised money for charitable causes, including the District Hospital.

Her work was continued by the Newbury Operatic Society.